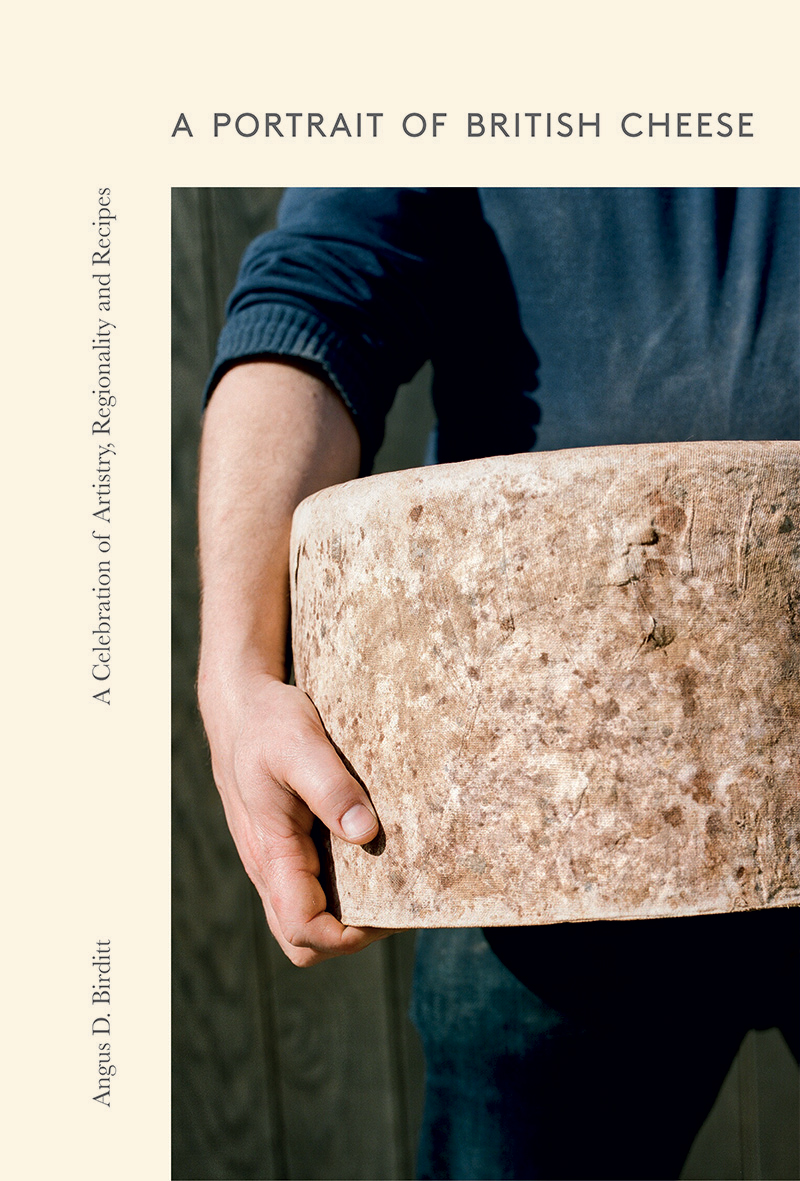

A Portrait of British Cheese: At The Table With Angus Birditt

Cheese, perhaps more so than any other food product, can help us understand the magnitude of love and labour that goes into making the food that we eat. Processes may take months or years, but we rarely stop to appreciate them. Over the last two years, Angus Birditt has been researching this very subject, culminating in his book A Portrait of British Cheese. We sat down to chat about the book and Our Isles, the platform he founded to celebrate the rural environment and the British Isles through food, nature, history and heritage.

Angus, tell us a bit about your story and how Our Isles began?

Well, I suppose I have to go back to my love for the natural environment. I have always lived in the countryside, either in rural Cambridgeshire throughout my childhood, surrounded by arable fields and mixed woodlands, or in North Wales after university, where I really started to take foraging seriously and experience new landscapes and wildlife. The countryside is where I find most of my inspiration for writing, photographing, curating and, well, eating!

“The more I delved into the world of cheese, specifically artisan and farmhouse cheese, I was amazed by the idea that someone could craft such delicious morsels of food directly related to the soil. I loved that these cheeses were not only a wonderful, delicious food product but also an instrument to express heritage, tradition and history.”

Besides my love for the natural environment and a real desire to celebrate what was going on in it, hopefully conserving it in someway, Our Isles was kick-started in essence when I started The Bridge Lodge, a small food company which sold a range of foraged products like wild garlic pestos and wild garlic sea salt. We hosted monthly supper clubs, often cooking 5 different courses each evening to celebrate the wonderful, regional food and drink we have in the British Isles. One memorable supper club was called SEA, a 5-course meal that celebrated the amazing seafood we have just off the isles like Conwy mussels, Anglesey lobster, razorclams, you name it.

Running The Bridge Lodge was hard, repetitive work making thousands of products by hand. However, as much as I moan about the production side of things, it opened up a world of food and drink as we visited local farmers markets and national food festivals selling our products. This was also when I started to write about food: the ingredients we were foraging, producers we were collaborating with – Halen Môn, for example, the salt harvesters that we teamed up with to make our wild garlic sea salt – and other food producers at the various markets and festivals we would meet including farmers, cidermakers, and cheesemakers.

Over time, I had created a treasure trove of words and photographs (by this point I had found a camera to snap away with!), but with nowhere to house it all, so that’s when I decided to found Our Isles, a place for all of my work to come together. It now also encompasses other rural creatives, sharing and supporting them as much as possible as we do in our online editorial, Stories within Our Isles.

Ultimately, Our Isles is a platform to explore and appreciate subjects like artisan and regional food, nature, rural history and heritage. I want it to be seen as an advocate for the rural environment, you could say. I want people to see Our Isles and be inspired themselves, to conserve the natural environment in a way that makes them happy and fulfilled.

Why cheese? What is it that made you want to explore and document the subject?

Cheese has always been an integral part of my life, from growing up, stuffed in packed lunches, or in recent times, melted on god knows what! I love trying regional food and travelling to different regions in the British Isles, so artisan cheese seemed to be the perfect food product that expressed the former and allowed me the excuse to travel.

What I found fascinating about artisan cheese is how many different varieties you can have from the same initial product, milk (which, of course, is so complex in itself). A Portrait of British Cheese began as a passion project. I visited several artisan cheesemakers around East Anglia where I grew up and in Wales where I am now living. I found myself starting to collect a body of work (photographs and prose) on various cheesemakers across the British Isles, fascinated by their deep knowledge of their local landscape and ecosystem, and their care for their animals.

The more I delved into the world of cheese; specifically artisan and farmhouse cheese, I was amazed by the idea that someone could craft such delicious morsels of food directly related to the soil. I loved how these cheeses were not only a wonderful, delicious food product but also an instrument to express heritage, tradition and history. Graham Kirkham of Kirkham’s Lancashire (1 of 30 artisan cheesemakers in the book) said that ‘every piece of cheese is a part of history’, his cheese being made to the same recipe his great grandmother made. You could be eating a food that someone was eating centuries ago.

You describe cheese as ‘the product of a magical symbiosis between land, livestock and producer’. Tell us a little bit about this and the meaning of food provenance. Why is it more important now than ever?

When I speak about cheese being ‘the product of a magical symbiosis between land, livestock and producer’ this is relative to farmhouse cheese. It is one of those rare food products can be spoken about in the same sentence as terroir – loosely defined as ‘evoking the character of the land’ or more broadly, the ecosystem. Farmhouse cheese certainly does this; it’s a synergy between the soil on which the pasture grows, the animals that graze, the quality of milk produced and the maker using the milk to produce cheese. And each aspect (soil/land, pasture/feed, animal, milk quality, maker) is so variable, which makes cheese such a diverse and fascinating product.

You mention three stages of cheesemaking: farming, making and maturation. How do each of these stages have an impact on the cheese that we eat?

Farming – as many farmers and farmhouse cheesemakers are finding out – is arguably the most important stage in relation to the health of the land, animals and the consumers. Farming forms the building blocks of food, and in terms of cheese, it’s the foundation for determining the quality of milk used for cheesemaking. Factors like the health of the soil and the welfare and diet of the animals are things to consider in this case.

The farmhouse cheesemakers I have visited work to the highest levels of animal welfare, and many are looking to become more sustainable with what they are putting onto the land and feeding their animals for the best possible milk for cheesemaking. Several are trying to be self-sufficient, growing as much as they can on the farm and reducing expensive inputs like imported grain or soya to feed their animals. Farmhouse cheesemakers are also increasing the diversity of pasture their animals are grazing to see whether it affects the final flavour of the cheese. It’s such an interesting subject and one that I’m always learning about.

For the making side of cheese, timings, temperatures, length of making, milk handling, weather conditions, among many more variables, all affect the make. I have tried to lay out the foundations of making cheese in A Portrait of British Cheese as clearly much as possible, as it’s such a complex subject.

Then, the maturation affects the flavour of the cheese. According to the cheesemaker’s preferences, aspects such as humidity, salinity, airflow and temperature are controlled to mature their cheese. The specific ecosystem and microbiome in the maturation process also affects the flavour of the cheeses, the microbiome being, again, like every aspect of the cheesemaking process, utterly fascinating.

Why and how should we be supporting British cheese right now?

Where and when you can, we should be buying directly from cheesemakers – many have websites with online shops – and/or cheesemongers and farm shops who work closely with artisan cheesemakers. We should be supporting them like this as the makers get more income from selling their cheese in this way and it builds relationships, with you, the customer.

How can we connect with the land, farmers, cheesemakers and methods that produce our food?

I always think there should be a GCSE in food provenance or the like to help our younger generations really know where and how our food is produced. But anyhow, I won’t rant! There are plenty of organisations and charities out there that can help connect us with farmers and food producers. The likes of Sustainable Food Trust, Pasture for Life, the Food, Farming & Countryside Commission, LEAF, FarmED, are just a few places to explore that try to untangle the crazy complexities of our food and farming industries, from both ‘top down’ and ‘bottom up’.

What should we be looking for in the cheeses that we buy, and how do we know if they really are made sustainably or regeneratively? Are there particular places we should be looking or buying from?

It is difficult to know exactly what we are buying, whether that’s buying cheese or any other food. So I would always try and buy as local and seasonal as possible; buying as closely to the producer, whether it’s your dairy products, vegetables, fruit, cereals or meat. I always try and do my research before purchasing. You can always head to your local cheesemonger or farm shop and ask where their cheese is from. They are a friendly bunch these cheese folk, and I’m sure they would be happy to chat about their cheeses.

Tell us about one cheesemaker in the book – what do they make, what’s their story?

Cheesemaking on the farm is based on the principle of the circular economic, reusing everything. I tried to focus on those cheesemakers that were as self-sufficient as possible. Two cheesemakers who exemplifies this are Patrick and Becky Holden from Holden Farm Dairy in West Wales, who make Hafod cheese, a Welsh Cheddar. They farm Ayrshire cows, a native breed, and graze them on species-rich pastures on the farm. They have been organic since the 1970s and now produce one of the best Cheddars out there – check them out!

Angus’s Pantry

1. Halen Môn Sea Salt

2. Pimhill Farm Muesli

3. Ground Coffee

4. Pot of local honey

5. Organic veg stock cubes

Read more: A Portrait of British Cheese

An exploration of the people, processes, stories and histories behind the incredible cheese made in the British Isles, A Portrait of British Cheese is a beautiful, thoughtful book that charts 30 farmhouse cheesemakers around the UK. Through interviews, stories, recipes and photography, the book celebrates how British cheese is profoundly connected to the land, farm animals and people involved in making it.